The hearse I’m riding in is a classic model: long, low to the ground, gunmetal grey. It has seat belts but the funeral director didn’t buckle up, so I assume we won’t need them. We’re traveling about 10 miles an hour on an upgraded cow path, a gravel trail that follows the curve of a West Virginia hill. The grave site is at the top of a hill overlooking a large pond with winter geese and a milk carton camera-ready herd of grazing cows. We talk as he steers around the ruts that are softening in the mild February sunlight. He appreciates the appeal of the old-fashioned term: “undertaker”, although he prefers “Director”. I say I understand but “undertaker” is a word that suits his profession and well as my own: to undertake good goodbyes.

This is a young man who understands how to turn endings into beginnings. He inherited his father’s farm and leased his legacy for a different kind of crop. Turning a pasture into a graveyard is a practice that dates back to the Civil War. Churchyards couldn’t hold all the dead, or the trauma from the bloody loss of so many young men. Idyllic pastoral scenes straight out of Psalm 23 were planted in villages and cities, a landscape of loss. Not everyone came equipped with cows, of course. It’s a view I can appreciate, and wonder if Martha, the guest of honor at this parting ritual, would have appreciated the irony of holy cows and country roads at her end.

I’m wearing a purple dress under the severely gray overcoat. It felt like a necessary gamble, given what “they” say about purple. A few may remember the poem, “When I am old, I will wear purple.” Far more are suspicious of my choice of clerical attire, being supporters of the ban of a book, The Color Purple. The ban started in 1984 and continues into the present which is definitely not excepted or accepted.

When I come into the funeral home and see the photo of Martha in her Geneva gown and her purple stole, I smile and hang up my coat with sense of conviction. I wear purple for Martha today because it means more than I know or need to say. Purple: it’s Lent. Purple connects some of the women in the room to the rite of ordination, to be a woman of the cloth. Purple connects Martha to Lydia, a fashion designer, an early convert to Christ, a founder of mission and churches, a woman of means.

It is also a dangerous color. Jerry Falwell has just denounced Tinky Winky, the purple baby-show character for being gay. that wears purple. You can literally hear the unspoken as I greet my clergy colleagues and members of Martha’s family. “Does this mean she’s a lesbian? Does this mean she thinks lesbians should be ordained? Was Martha a lesbian?

The answers to the questions are: No. Yes. I don’t know. She never said. No one ever said. I assume they assume I know. Not being told gives me the ability to be dove-open and snake-smart. I mix it up. Purple is the color of lent, of Lydia, of bishops, of lesbians, of lesbian bishops, and the color of atonement. There’s the purple cloak of Pilot, the color of advent and expectation, the purple prose for when I am old. I will wear purple then. I wear purple now.

I am sure the community of friends will try to decide what it meant; the community of family will not mention it at all, but nod at each other as if they knew.

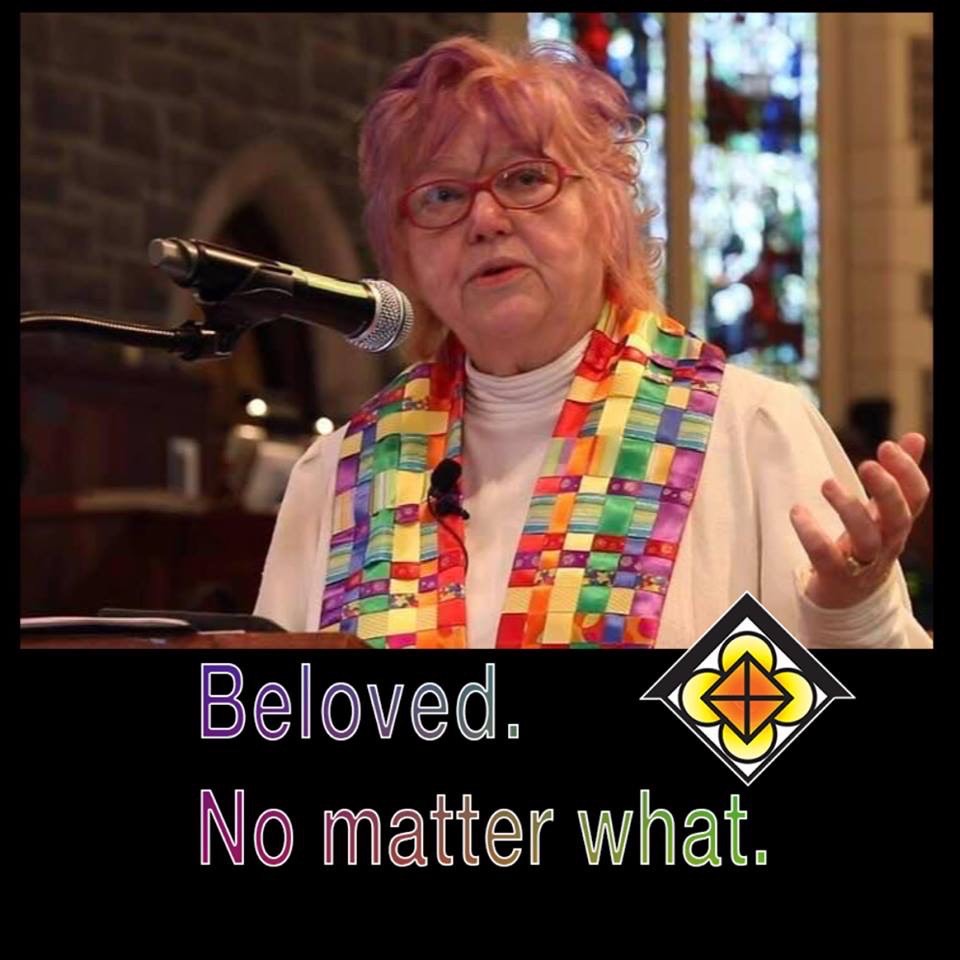

I wear a stole I found on the way. It was waiting for me in Almost Heaven. It’s a woven black background shot through with primary colors. It’s hand-made by a woman to be worn by a woman. Its purpose is warmth as well as beauty, and that makes it holy and human. It also makes sense of stole-wearing. I need its protection and its authority. The theological meaning is woven into those human needs as a second layer against cold funeral wind.

Martha earned the right and the rite of stoles the hard way. She’d been the first WV clergywoman elected as a delegate to General Conference, first leader of the Commission on the Status and Role of Women. After years of leadership, she laid her right and the rite aside; no one took it from her. I sat beside her in the chapel balcony when her name is read as “retired”. “Why? Why now?”, I whispered. Her quiet answer has echoed through the years. “Sometimes you have to leave the church to save your soul.”

Martha: a woman of the cloth

a woman of coal

a woman of Christ

a child of God

no matter what people say

My task as preacher and liturgist is to protect and risk and witness. I ask Frank, who wears the dark suit of male/clergy/superintendence well, to read her obit, and speak of her worthiness, her work for the church, the conference, and unchurched world she’d served so well. He speaks for her, but also for the many others who have served Christ in silence, lest they be called “unworthy”.

I wear purple with a handmade stole of black with rainbow colors. I preach the gospel I find in the work she’s finished and left behind. I touched lightly on the last memory I have of Martha’s conference leadership: a resolution providing funds for child care for women, lay and clergy, who serve on conference committees. She, without children, wants mothers with children to be able to serve.

Her proposal sets off a fierce floor fight. Old patterns of motherhood and ministry are summoned to defend against this assault. Her primary opponent cites his wife’s “truly Christian” way of stay-at-home churching that is biblical and economical. Martha has prepared for the battle well however; the proposal passes by a slim margin.

The last liturgical act of the United Methodist clergy funeral is the awarding of The Circuit Rider plaque for the grave. It is our Wesleyan story of service for all to read: where ever there was need, there was a Methodist. The district Superintendent is assigned to hand this award to Martha’s oldest brother who will carry it to the graveside. He’s the pastor who lost the floor fight years before. It heals that old wound to hear him speak so well of Martha, and to see the reluctant paternal side of her house receive the gift of her ministry.

The coming parting of the United Methodist ways may be delayed by this pandemic afflicting us now. I will, however, be grateful for God’s sense of humor and justice in gifting us with each other. May we all rest in peace and rise in power.