How does one pray during a pandemic? Are there performative forms of lament or grammars of grace that articulate sighs too deep for words in times like these? Individuals and institutions have begun collecting prayers like precious rain-water. I read words on scrolling screens along with unknown others in virtual reality. On some bone-dry days I pour poetry into my eyes; I sing along with Rising Appalachia or Aretha Franklin. Singing together will be a dangerous act, a deadly conspiracy when the doors of the church open again.

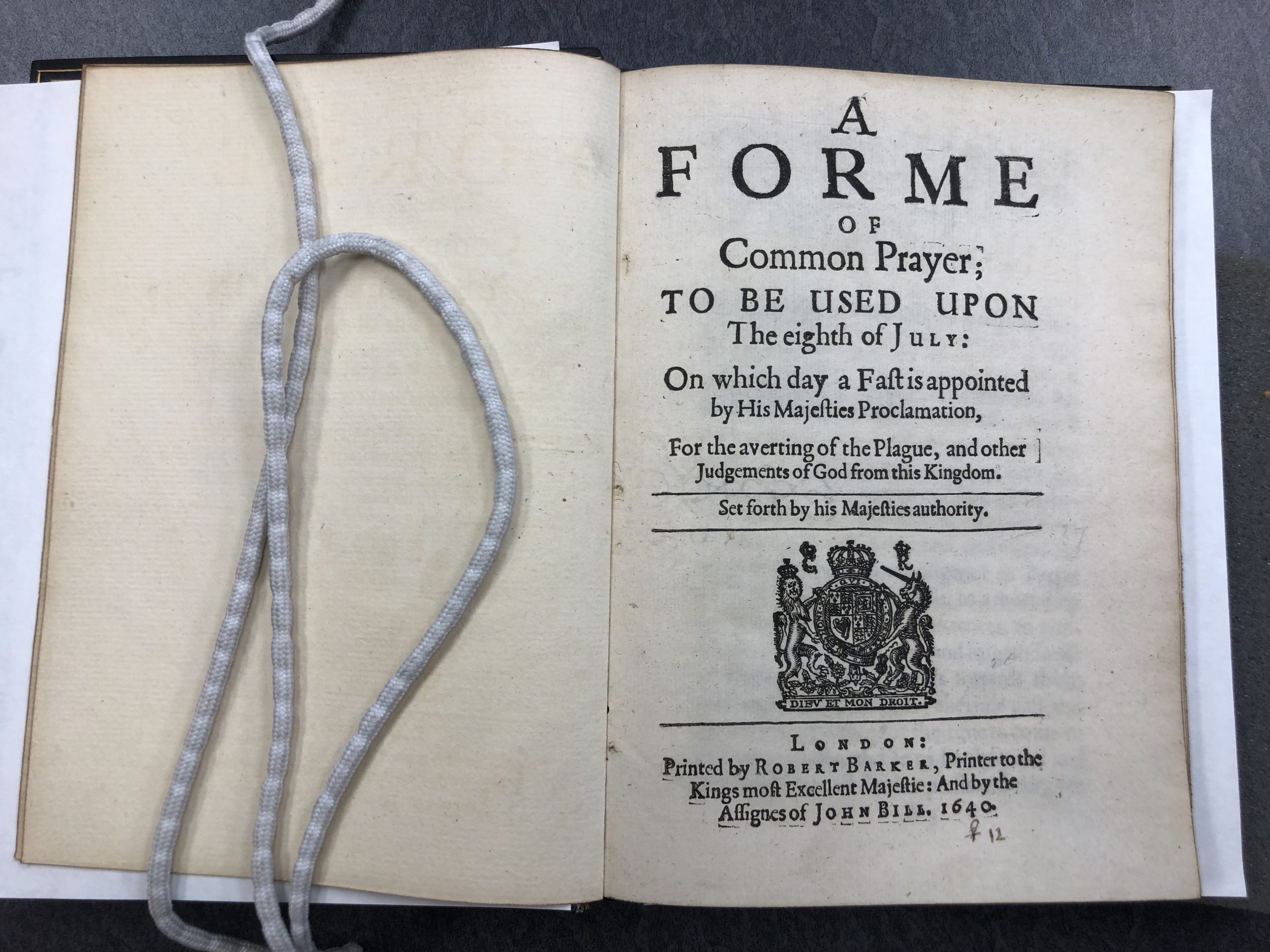

My pandemic prayer quest retrieves a text in Drew’s archives, courtesy of Jesse Mann and Brian Shetler. The title page spells it out. “A Form of Common Prayer, Together with An Order of Fasting for the averting of God’s heavy Visitation upon the many places of this Kingdom, and for the drawing down of his Blessing upon us, and our Armies by Sea and Land.” It includes a set of instructions: “The Prayers are to be read every Wednesday during this Visitation, Set forth by His Majesty’s Authority.” Anno 1625

I dig out my church history notes to figure out which majesty provides the prayers and orders fasting: Charles the First. These prayers appear the same year that Charles ascended to the throne of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Charles took his conviction of the divine right of kings seriously. That conviction is clearly set forth The Preface:

“We be taught by many and sundry examples of holy Scriptures, that upon occasion of particular punishments, afflictions and perils, which God of his most just judgement hath sometimes sent among his people, to show his wrath against sin, and to call them to repentance, and to the redress of their lives, all men ought to be provoked and stirred up to more fervency and diligence in prayer, fasting and alms-deeds, to a more deep consideration of their consciences, to ponder their unthankfulness and forgetfulness of God’s merciful benefits towards them, with craving of pardon for the time past, and to ask his assistance for the time to come, to live more godly, and so to be defended and delivered from all further perils and dangers. So, king David (2 Sam. 24.14) in the time of plague and pestilence which ensued upon his vain numbering of the people, prayed unto God with wonderful fervency, confessing his fault, desiring God to spare the people, and rather to turn his ire to him, who had chiefly offended in the transgression. The like was done by the virtuous kings, Josaphat and Ezekias, in their distress of wars and foreign invasions.”

I consider this claim: a national leader should pray with fervency, confess his faults, and ask God to spare the people. Scriptural reasoning and a tradition of divine right holds a leader accountable for the transgressions that have provoked God’s just judgement of plague. His “majesty” is confirmed by God’s majesty, therefore when the king prays, the Holy One hears.

Intercessory prayer by the King for the people does not, however, remove the obligation of the people for “more fervency and diligence in prayer, fasting, and alms-deeds”. Alms-deeds is a compelling combination, an open-handed service of time and money offered in defense of any good community that wishes to survive.

“Particular punishments” are evidence of the existence of a just God who has “visited” this pestilence on God’s people. That theological conviction is not held in common now. An unquestioned equation of suffering = sin was challenged in the book of Job, and by Jesus, but it’s not hard to find pandemic prayers that invoke the same cause and effect. The nation has sinned, and the evidence cited ranges from forgetfulness of God’s mercy to specifics: abortion, homosexuality, sexual immorality, corrupt leaders, corporate greed, racism, xenophobia.

There were lists of individual and corporate sins in the 1626 prayer book, including economics: “Also that our trades and traffic is become the practice of deceit, and theft, while we make our gain by lying, forswearing, false measure, false weights, and false lights, which are an abomination unto the Lord…”

The chief sin is ascribed to any who challenge to those in authority. They are framed by scriptural references to people who are “factious and seditious conspirators” and murmur against their God-appointed leaders. “The people of Israel murmured and rebelled against Moses and Aaron (Num. 16) their leaders: and there have been also among us in England not only such as have despised government, and spoken evil of those that are in authority: but such also as S. Paul (2 Tim 3.4) prophesied of, that there should come in the later days traitors, heady, high-minded murmurers, malcontents, fault-finders, as S. Jude calls them(Jude 8)

Prayers for the king and his family are included but it is striking that a prayer for Parliament is included for the first time in this 1625 Prayerbook, designed to be read aloud in session. Here is a poignant reminder that we have inherited forms of prayer that have yet to be demonstrated in a common wealth of happiness and blessing.

“And they are come into thy house in assured confidence upon the merits and mercies of Christ (our blessed Savior) that thou will not deny them the Grace and Favor which they beg of thee. Therefore, O Lord, bless them with all that wisdom, which thou knowest necessary to speed, and bring great Designs into Action, and to make the maturity of his Majesties and their Counsels, the happiness and the blessing of this Commonwealth.”

Charles the First assumed the throne on March 27, 1625, believing in the divine right of kings and his role as head of the Church. He observed daily prayers and the eucharist, and was known for his love of Anglo-Catholic liturgical life. The prayer books for 1625, 1636, 1640 offer scriptural and liturgical resources for a nation suffering the devastations of plague, economic collapse, and war. Perhaps Charles believed the proper rites could guarantee right rule. He fiercely enforced the use of the Book of Common Prayer on England, but triggered a rebellion in Scotland over the attempt. His repeated losses in English Civil wars in 1642, quarrels with the Parliament he ordered prayers for, and his conviction that he was answerable only to God led to his execution in 1649. His Archbishop, William Laud, also beheaded by Parliament, named the dilemma: “A mild and gracious prince who knew not how to be, or how to be made, great.”[i] A leader who doesn’t know how to be great or what it takes to make his nation great loses more than his head; history records him as a fool.

The prescription of alms-deeds, prayer, and fasting as a national response to plagues, pestilence, and pandemics still seem like good medicine. Certainly, there are pastors now who are gathering their people virtually as faithfully as the pastors of the 17th century.

“Let all Pastors and curates exhort their Parishioners to come to the Church, with so many of their families as may be spared from their necessary business (having yet a provident response to such assemblies to keep the sick from the sound while in places where the Plague reigns) and they to resort thither, not only on the Sundays and Holy days; but also on Wednesdays and Fridays during the time of these present afflictions: exhorting them to behave themselves there godly and reverently, and with penitent hearts to pray unto God turn these Plagues from us, which we though our unthankfulness and sinful life have deserved.”

There were also orders for social distancing, and the guidelines based on the best that science and philosophy had to offer. These were communicated in An Exhortation Fit for the Time that was to be read every time people gathered.

“Again, because in this great mortality of ours, we find by experience, that not so much any general corruption of the air, nor any distemperature of the blood, or humors of men’s bodies have been the causes of the spreading and continuing of this infection, as the contagion that the disease itself has bred, in which one man receives from another, the sound from those that are sick: Therefore also men are to learn that one chief and ordinary means of their preservation in this dangerous time is the avoiding of the contagion that comes by mingling disorderly the sound, and the sick together. And if there be any that being yet sound do think they are not bound in conscience to shun and avoid the persons and places that are infected, except it be in case of necessity: or if those that are diseased or do keep in houses where the disease is known to be, shall think much that are that they are shut up and restrained from coming abroad, or frequenting the common and public assemblies of those that are clear having in the meantime such things as are necessary for their sustentation They must be content to hear out of the word of God their error therein and ignorance.”

Error and ignorance of the Word of God is demonstrated by those who will not keep in houses or avoid persons and places of infection. There’s even a reference to the necessity of “lepers” wearing masks in public as evidence of their faith in God and concern for the public good. An assertion of individual rights over welfare of others, and armed threats against those who serve in Congress are unmasked forms of rebellion in any age.

There is one collect and one biblical citation in these prayer books of the time of England’s plague I carry into my prayer life now in this time of pandemic.

The first reading is from Joel. It is to be read with a loud voice at the start of the prayers:

“Rend your hearts and not your garments, and turn to the Lord your God, because he is gentle and merciful, he is patient, and of much mercy, and such a one that is sorry for your afflictions.”

The third collect is for any time the shadows threaten to overwhelm the light.

“Lighten our darkness we beseech thee, O Lord, and by thy great mercy defend us from all perils and dangers of this night, for the love of thy only Son our Savior Jesus Christ. Amen

May the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God, and the fellowship of the holy Ghost, be with us all. Alleluia

[i] Gardiner, Samuel Pawson (1906), The Constitutional Documents of the Puritan Revolution 1625-1660 (Third ed.) Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 83