Rubbish. It accumulates with and without our help. In corners and in conversation we litter our lives. Some rubbish can be clearly identified; trash is trash, but we may need lessons in how to sort trash these days. Recycling is not simple; single-stream or source separated?

So, God don’t make no junk, but we two-legged do. The really tricky part about rubbish isn’t the unimportant stuff we insist on keeping. It’s the stuff other people dump on us. We store it in the back rooms of our minds: the times we feel discarded, labelled “worthless”; the shame that never disappears, names that demean, denial of dreams, the refusal to listen, the pain of having your truth declared nonsense. That’s rubbish!

It’s not passive stuff. Refuse piles up in your corner, fills your foundation, it takes on a life of its own. It subdivides and multiplies when you’re not watching. If there’s a line, it will erase it; it crosses boundaries. The noun becomes a verb. You can rubbish someone, criticize severely and reject as worthless. To rubbish is to deny the holy humanity of another.

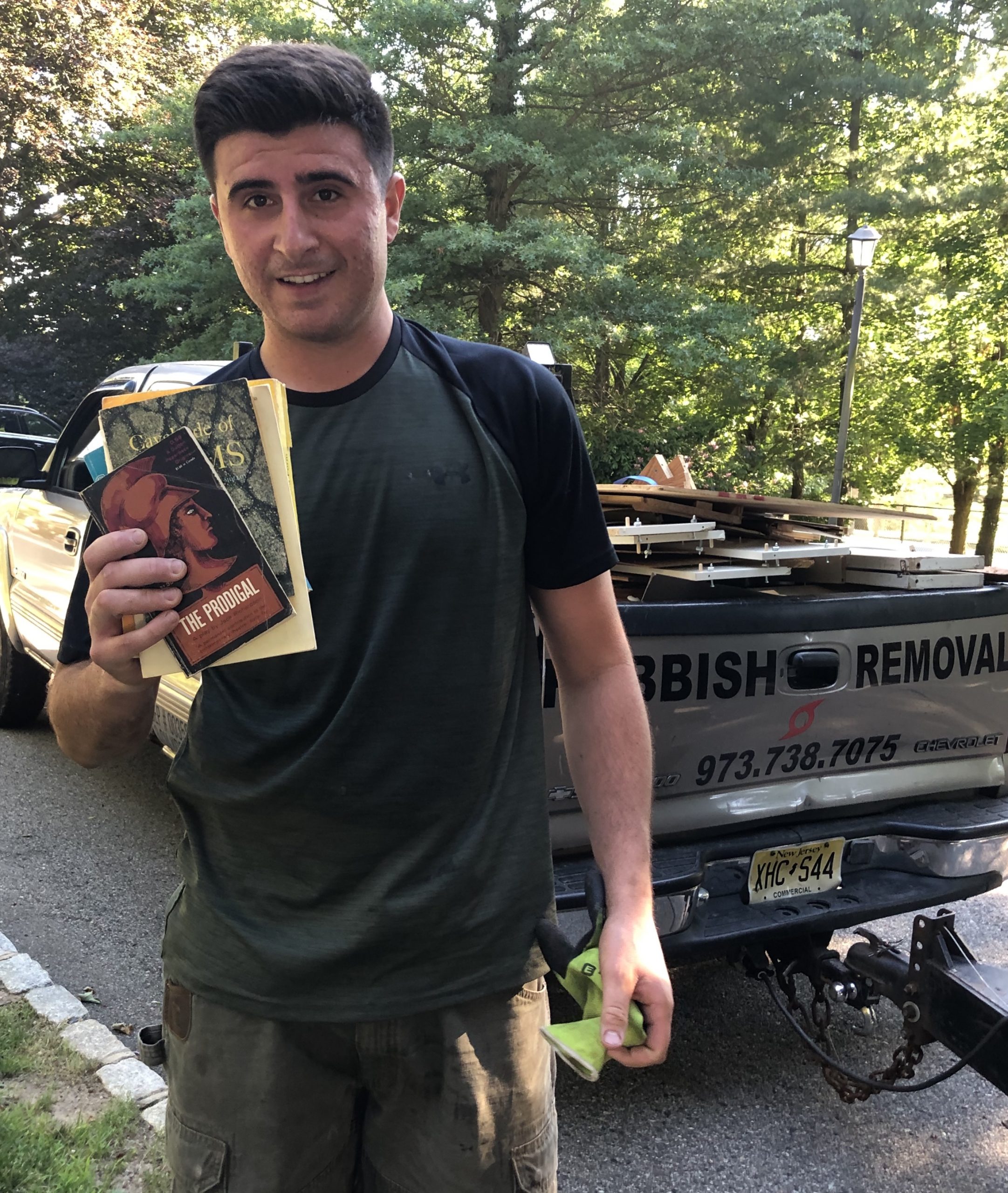

So, what’s the solution? Who you gonna call? The Rubbish Removers. No, seriously, been there. Done that. They arrive and cart away all your rubbish, no questions asked. You pay by the yard. They load, and then it’s gone.

Of course, if you’ve got live wires buried in the ruble, they can’t help with that. You’ve got to call a higher power to break the connection. It’s hard work, disconnecting from rubbish. I found myself still wired over a scholarship I didn’t get. The short version of the story involves a doctoral scholarship, my application, and a dean. You had to apply, send your essay to your MDIV alma mater; they select several for consideration and send them (application + essay) on to the UMC committee.

I’m desperately needy, and I have original research and great recommendations. The date comes and goes and no news. Not good, not bad, nothing. I call the Dean of Duke’s office to check, and his assistant says, “Not a problem. We’ve got all of them here in the files. We received yours.” When I tell her the filing deadline was past, I get silence and then a brisk, “I’ll let him know.”

I didn’t freeze up; I call the head of the Committee and asked if they’d received any applications from Duke. The answer was no, but the awards have been announced and that is that. My response must have been more than “Thank you.”. The next day I answer the phone and discover I’m talking to the Dean of Duke Theological School.

I listen politely, more than a little surprised that he actually called. What I’m hearing is his calm and kind explanation that my work had simply not measured up to the other Duke graduates who’d applied. It was not worthless; it just wasn’t good enough.

I let him finish, wait to get my breath, and then say, “Rubbish. Let me tell you what actually happened.”

I’m calm; I have a deep cold snake state I get in when I’m really angry. There were other applicants who were overlooked; others who might have needed the money more than I did. There’d been a mistake. He made a mistake. Mistakes happen. Mistakes are not fixed by lying.

He’s quiet, then asks, “What is it that you want?” I’m not sure what he expects, but it isn’t my answer. “What have you done to the Apostles’ Creed?”

He repeats my question like I’ve lapsed into gibberish. “Forgiveness of sins,” I say. “Why have you, a dean of a theological school, forgotten that part of the Creed?”

A long pause is followed by one concession, “Mistakes have been made.” He agrees to let the unknown others in his file know what actually happened to their forms.

So that was that. Rubbish and being rubbished reminds me how desperately I need to believe in “the forgiveness of sins”. Forgive us our sins as we forgive others is a terrifying prayer. The Rubbish Removers can’t budge this stuff. Only the Beloved, whose last human prayer was, “Abba, forgive them. They don’t know what they’re doing.”

I believe. Help my unbelief.