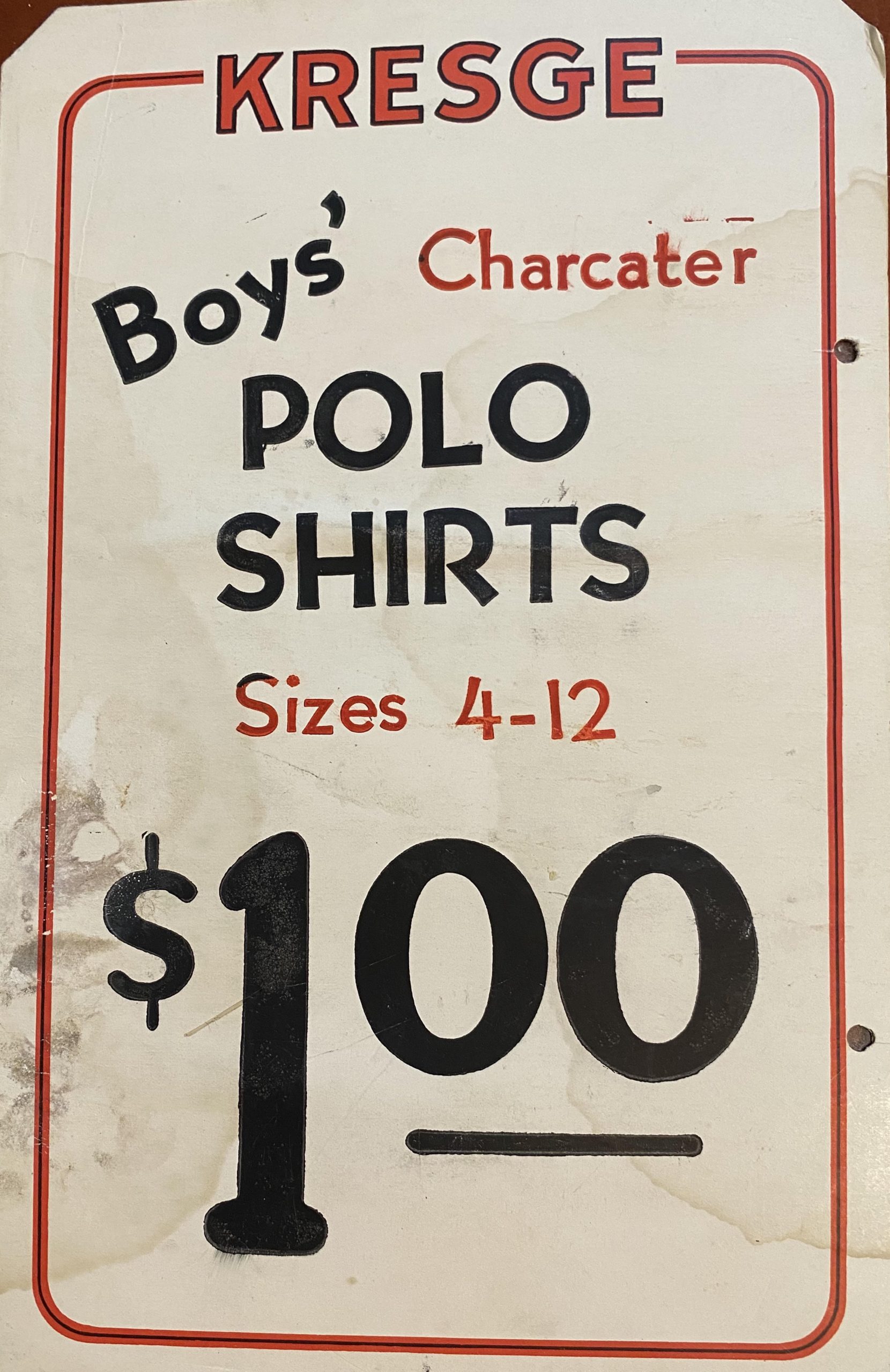

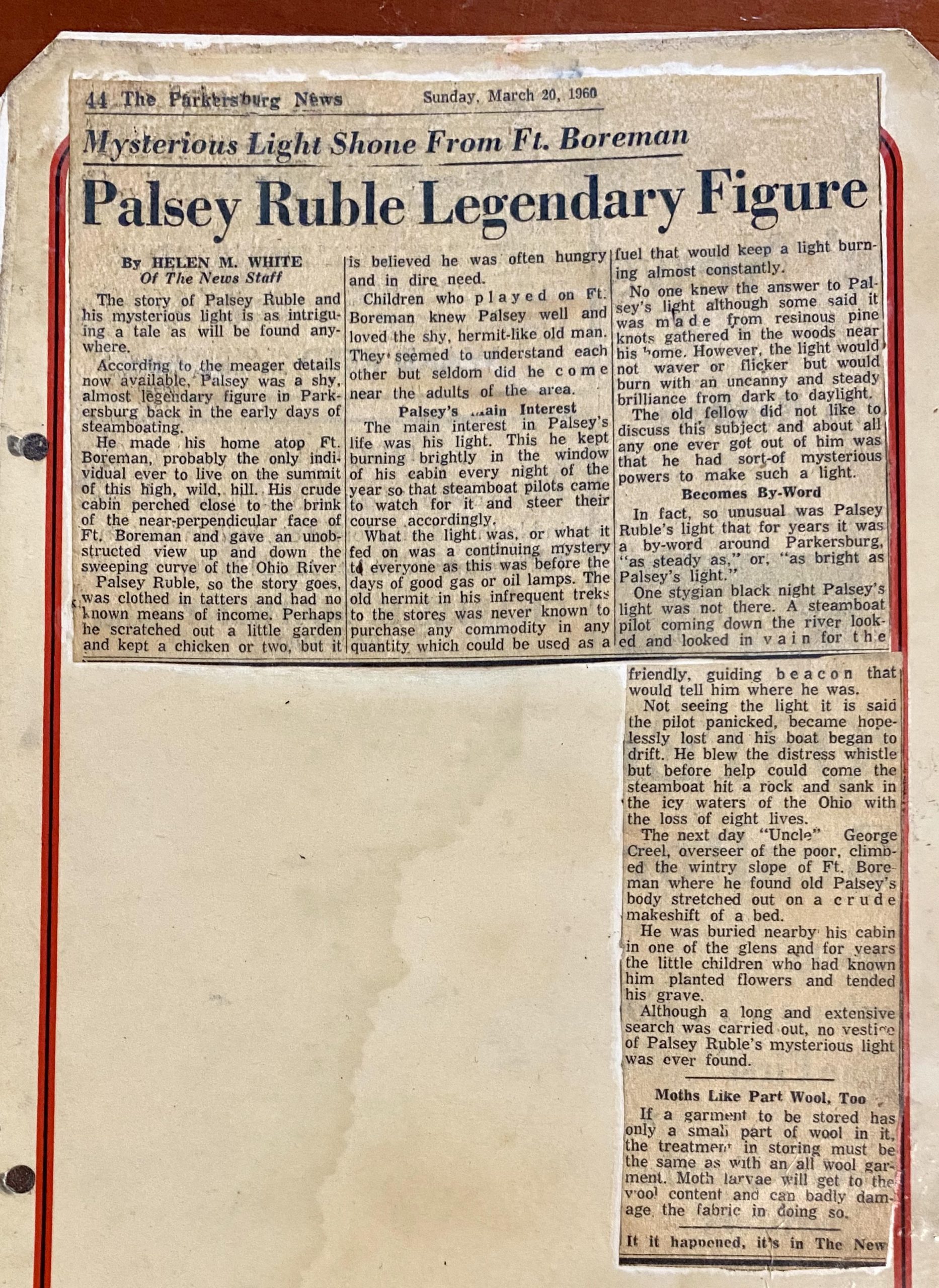

It was a gift. It was a burden. It threw a bright light. It cast a long shadow. It came to me in a simple way. It has remained with me for sixty years, convoluting my consciousness. It’s a news clipping, March 20, 1960, The Parkersburg News, West Virginia. It’s laminated for some mysterious reason on the back of a Kresge’s sign offering boys’ character polo shirts for $1.

Great Aunt Bess, who wore yellow ribbons in her hair at 98 and sang “Sweet Little Buttercup” every time she came down the stairs to welcome company, is responsible for this in my life. One Saturday morning, she lifted this from the rubbly treasures of her house and put it in my hands. “Here, dear, learn something.” And so I have, for better for worse.

This is an old news story about a signal light and a sandbar. In the early days of steamboats that carried cargo and delivered a love of river adventures to Americans, there lived a man named Palsey Ruble. He did not captain the big paddle wheelers; he never rode on the Queens of the waterways. He lived beside the Ohio, high on a bluff overlooking Fort Boreman. Helen White, writer of the article describes it. “His crude cabin perched close to the brink of the near-perpendicular face of Ft. Boreman and gave an unobstructed view up and down the Ohio. River.” This was then, Western Virginia, before the war that created West by God Virginia.

Palsey Ruble, as the story goes, wore rags, and came to town so rarely that few self-respecting grownups ever greeted him by name. But their children knew him, not being concerned with sensible behavior, they would play at the foot of his high hill.

A strange man. Outcast and rejected. Perhaps a man of sorrow and acquainted with grief, but also a man with a secret. Palsey Ruble had a light. A signal light. A light that came from his single window and shone so brightly over the river below that the steamboat pilots came to watch for it and steer their course accordingly. They would take their soundings to check for the treacherously fluid sandbars and they would watch for Ruble’s light.

A light in the darkness, a steady presence that burned night after night from dark to daylight. A signal light for the boats that passed below him on their way to places far beyond his sight. A steady beam in the dark. After a time, Ruble’s light entered the language of the community in a way that he did not. “Steady as a Ruble light” they would say or “bright as Palsey’s beacon.”

His light. A simple thing. A secret thing. No one knew how it came to be or what made it burn so bright. This was before the days of good gas or oil lamps. Perhaps it was a candle but everyone agreed it never flickered. It never wavered. It burned brilliant in the darkness, and disappeared at dawn. The children teased for an answer. Some adults nosed a question at him when he came to buy supplies from town, but he never explained the source; he never revealed the secret. The most he would say was that the light came from a mysterious power known only to him.

One night. the light was gone. A steamboat pilot coming down the river searched in vain for Palsey’s beacon. The light was gone. Without the light or a moon to guide, the pilot panicked and the boat began to drift. The distress whistle sounded again and again but before help could come, the boat hit a sandbar, then pulled loose by the current, slammed into the rocks and sank in the icy waters. Eight lives were lost.

The next day, George Creel, the overseer of the poor, climbed the wintry slope of Fort Boreman. He found Palsey’s body stretched out on a makeshift bed. They buried him in the glen, near where the children played and the children decorated his grave for years. His cabin was searched his cabin and the surrounding cliff and down to the river’s edge. The source of Ruble’s Light was never found.

An old story. An odd story, given to a ten-year old to learn from. How it drifted from its moorings and lodged on my sandbar of memory, I can’t explain. I only know it gathered light as well as shadows as I grew.

Listen to the sound of its sounding:

What is the role of an artist who is a believer?

To illuminate truth.

What is the source of that light?

If we know, we cannot tell. It is mystery.

It comes to; it does not come from the artist.

It makes us transparent to the world. It throws the world into shadows.

It burns us without our permission.

It is all we know of God.

Does holding the light create an outcast?

Yes and no. Yes and no.

We burn for the sake of the neighbor, who may think us strange.

We catch fire from commonplace things.

We are not capable of sensible living.

We belong to this time, this place, this household of faith, but why are we so lonely,

ill at ease, used, but not blessed, needed but not nurtured.

Why do just the young in heart, those innocent of power,

why do just the children know us by name?

Does the light give you power? Why pretend that the world does not see you?

How to account for the arrogance of art or any claim to guide the destiny of others by the light of sheer dreams?

Palsey Ruble, break your silence. Did you ask for the light? Did you know what it meant? Was it enough to quietly stand and shine into a darkness that both needed and rejected you?

Did you turn bitter from the slights, the disrespect of others? Did you plunge your light into icy despair? Did you go from holding the light to claiming the light? Did it light your way to heaven? Did it burn you into hell?

And speaking of signal lights and sand bars, are there some so gifted among us, that when their light falters, when their life fails, we who depend on their guidance go adrift and drown? Is it better to travel in darkness than to seek the light at all?

A story from the past that troubles the face of these waters, but alongside that story, I’ll line out a song. A song written when steamships carried our cargo of dreams, our common good of community. It’s a song we still sing in West by God Virginia, even though it’s not in the hymnal any more. It sounds best sung with the hills on one hand and the river on the other.

Brightly beams our Father’s mercy

From His lighthouse evermore,

But to us He gives the keeping

Of the lights along the shore.

Dark the night of sin has settled,

Loud the angry billows roar;

Eager eyes are watching, longing,

For the lights along the shore.

Refrain:

Let the lower lights be burning!

Send a gleam across the wave!

Some poor fainting, struggling seaman

You may rescue, you may save. Phillip Bliss, 1871

Here is a sounding of hope, a song to help us lay our burden down. We are called down by the riverside. We are keepers of the lower lights, called to light the shorelines, brighten the edges of chaos. There’s a desperate need of our lower lights. There is someone you may rescue. Hold your light steady and let it shine! Trust that God’s searching beam of Mercy will illuminate our dark night of the soul, guiding us home through the storms. Christ is the Light that encounters darkness and is not overcome.